Thirty years ago, an adult would self-medicate their anxiety by picking up a smoking habit. Today, we’re always looking for the next like.

For artists and capitalists alike, the ephemerality of social networks has created a renewed obsession with limited-edition runs. And to great effect. How can digital art be scarce? Set it to expire after 24 hours, release it only to select streaming services, or give it away for free for just one day, and do your best to ignore screenshots, copies, and bootlegs.

Soon we’ll realize we’re trying to create meaning where none exists. The record or novel resting on a bookshelf is no more significant than a few bits of data on a hard disk. But they are different: A work’s plastic and paper and ink combine to deliver a tangible sense of accomplishment, one that can be loaned to a friend or sold to an acquaintance. Digital work, on the other hand, is limitless by design. The ease with which we can duplicate a file is central to the business model of social media platforms–for up-and-coming musicians, a song is nothing if not on iTunes, Spotify, Google Play, Amazon, Soundcloud, Tidal, and Bandcamp simultaneously.

For those artists, maintaining a profile on a half dozen or more platforms feels like feeding a monster with an endless stomach. In between creating our work, we’re always typing the next words to publish or scrolling to the next comment to argue. What is it, though, that we’re replicating with digital experiences? The anxieties, the exclusivity, the capitalist’s ideal that everything’s for sale?

Previously, a young artist would buy a notebook and a pen and be left to their imagination. Today, social networks strip away the ability to look at a blank page or an empty box with wonder. Instead we’re nudged to the edge of the diving board, urged to immediately consider what must fill it: “Write something…” or “What’s happening?” they demand.

Yet clicking the share button doesn’t come with the satisfaction of a gallery opening or a deep conversation with a close friend; it just asks for more. Share with additional friends. Upload another picture. Browsing isn’t enough. Social networks need our pictures and statuses and other miscellany to show us advertisements and to give our friends something to creep on–so we all stay on the site longer and view more advertisements.

While social media provides important functions like television and radio and the telephone did before it, the transience leaves an emptiness. That void has forced software makers to dial up artificial indications of progress and success–follower counts, likes, hearts. These numbers breed a special kind of anxiety that tricks us into thinking we’re in a positive feedback loop when we’re not. Getting a retweet almost certainly does not change my life, and it does not make my writing better or worse. So why do I care how many people share this article? As Max Read summed it up (naturally, on Twitter, in a now-deleted tweet), “The business model of the contemporary internet is to create anxiety in its users so they feel compelled to engage.”

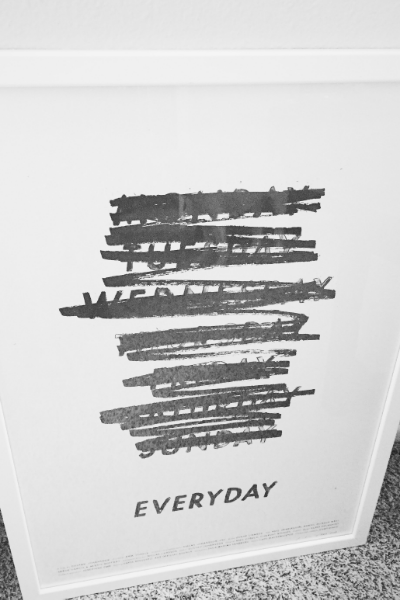

To soothe the anxiety, we’ve diminished the triumph of actually publishing in the first place, because the ease with which you can publish now correlates with the bottom line of a publicly-traded company like Facebook. Along the way, the constant stream of anxiety-inducing buttons and icons and statuses changed the art we create and consume. Now, it’s all about how much we share. Being prolific, at one point, could’ve been a way to cut through the noise. But because we never know what will hit, it’s become the standard mode of operation. Even great works of our time are met with a common response: “More!”

Once published, we’re competing with shared bits from other people and the algorithms of the platform, the modern-day gatekeepers. When our work doesn’t attract enough clicks in the first hour, the algorithm decides it’s not good and buries it in the backyard. To expand our reach beyond a few dozen loyal friends and family, we have to pay for ads. How can it be said “if you have good content, people are going to find it no matter who you are and where you are” when that’s the case?

This chase for numbers–or “engagement” as social networks like to call it–pushes us to judge work quickly. Even if the viewers don’t demand more, the algorithms do it for us. Autoplay, up next, playlists. Streaming from one piece of art to the next is easier than changing records on a turntable. And to exist online, all context must be stripped from the art–we no longer move past liner notes and acknowledgments with intention, now the platform may not even display them, making decisions to diminish or highlight certain features to promote engagement.

Playing to specific platforms’ quirks and limitations is half of what makes art today. To mimic some form of control, we’ve learned what gets clicks and what doesn’t. Instead of practicing repetition to improve a technique, we repeat tweets with slightly different phrasings to see which gets more likes. To thrive means to submit to the mechanics of social networks. Even Kanye West quickly tweeted, “Ima fix wolves,” after he released The Life of Pablo and saw his followers response to the absence of Sia and Vic Mensa in favor of Frank Ocean. This is the same unapologetic artist who told the New York Times in an interview preceding the release of Yeezus, “I don’t have one regret.” When Jon Caramanica asked if he believed in regret at all, Kanye added, “If anyone’s reading this waiting for some type of full-on, flat apology for anything, they should just stop reading right now.”

What does that say about our bodies of work, when each line in a song is up for hire? On the other hand, when everything is one click away from being turned into a meme, it’s no wonder why artists let self-censorship masquerade as self-preservation. And maybe that’s why Kanye decided to embrace a software maker’s approach to releasing an album: it’s never finished. Outdated versions will be replaced seamlessly thanks to streaming services, while bootlegs will be quietly passed around by hardcore fans. What’s lost to updates will be left to lore, a few bits of data existing in untold places.

Turning our art into a stream of updates is perhaps the logical conclusion to social media–hanging onto attention drip by drip is how we make it as artists today. Engagement is good, the social networks have trained us, whether or not the engagement is positive. And as we commit these acts of constant judgment, we’re robbing ourselves of the experience to fully process the art–to let the work challenge or reinforce our ideals, to push the boundaries of what we think we know, to consume it on the creator’s terms before we critique it on ours.

So the modern-day artist tries to take this into account, making art for everyone that matters to no one. The internet gave us free canvasses; its feedback loop killed the concept of prolific artists who create on their own terms. What those artists rarely ask of their audience, what the audience never stops to consider before hitting download: How can we care about any piece of art when we try to care about every piece of art?